Scotch whisky

| |

| Type | Distilled beverage |

|---|---|

| Country of origin | Scotland |

| Introduced | 15th century (active: 525 years) |

| Alcohol by volume | 40–94.8% |

| Proof (US) | 80–190° US / 70–166° UK |

| Colour | Pale gold to dark amber |

| Flavour | Smooth, sharp, (often) hint of vanilla |

| Ingredients | Malt, water |

| Variants | Single malt, Single grain, Blended malt, Blended grain, Blended |

| Related products | |

Scotch whisky (Scottish Gaelic: uisge-beatha na h-Alba; Scots: whisky/whiskie [ˈʍɪski] or whusk(e)y [ˈʍʌski]),[1] often simply called whisky or Scotch, is malt whisky or grain whisky (or a blend of the two) made in Scotland.

The first known written mention of Scotch whisky is in the Exchequer Rolls of Scotland of 1494.[2] All Scotch whisky was originally made from malted barley. Commercial distilleries began introducing whisky made from wheat and rye in the late 18th century.[3] As of May 2024, there were 151 whisky distilleries operating in Scotland,[4] making Scotch whisky one of the most renowned geographical indications worldwide.[5]

All Scotch whisky must be aged immediately after distillation in oak barrels for at least three years.[6][7] Any age statement on a bottle of Scotch whisky, expressed in numerical form, must reflect the age of the youngest whisky used to create that product. A whisky with an age statement is known as guaranteed-age whisky. A whisky without an age statement is known as a no age statement (NAS) whisky, the only guarantee being that all whisky contained in that bottle is at least three years old. The minimum bottling strength according to existing regulations is 40% alcohol by volume.[8] Scotch whisky is divided into five distinct categories: single malt Scotch whisky, single grain Scotch whisky, blended malt Scotch whisky (formerly called "vatted malt" or "pure malt"), blended grain Scotch whisky, and blended Scotch whisky.[6][7]

Many Scotch whisky drinkers refer to a unit for drinking as a dram.[9] The word whisky comes from the Gaelic uisge beatha or usquebaugh 'water of life' (a calque of Medieval Latin aqua vitae; compare aquavit).[10][11]

History

[edit]

The earliest record of distillation in Scotland is in the Exchequer Rolls of Scotland for 1494.[2][12]

To Friar John Cor, by order of the King, to make aqua vitae, VIII bolls of malt.

— Exchequer Rolls of Scotland, 1 June 1494.

The Exchequer Rolls' record crown income and expenditure and the quote records eight bolls of malt given to Friar John Cor to make aqua vitae over the previous year. The term aqua vitae is Latin for "water of life" and was the general term for distilled spirits.[13] This would be enough for 1,500 bottles, which suggests that distillation was well-established by the late 15th century.[14]

The first known reference to a still for making "aquavite" in Scotland appears in the Aberdeen council registers,[15] in a case heard in 1505 by the town's bailies concerning the inheritance of goods belonging to a chaplain named Sir Andrew Gray, who died in 1504. Among his goods was recorded (in Middle Scots) "ane stellatour for aquavite and ros wattir'".[16]

Aqua vitae (in the form of wine or spirits) was used when making gunpowder to moisten the slurry of saltpetre, charcoal and sulphur.[17] As a drink, Scotch whisky was a favourite of King James IV of Scotland.[18]

Spirit production was first taxed by the Parliament of Scotland from January 1644, with an excise duty of 2s 8d imposed per Scots pint; instigating the illicit distilling of spirits within the country.[19] Between the 1760s and the 1830s a substantial unlicensed trade originated from the Highlands, forming a significant part of the region's export economy. In 1782, more than 1,000 illegal stills were seized in the Highlands: these can only have been a fraction of those in operation. The Lowland distillers, who had no opportunity to avoid taxation, complained that untaxed Highland whisky made up more than half the market. The heavy taxation during the Napoleonic Wars gave the illicit trade a large advantage, but their product was also considered better quality, commanding a higher price in the Lowlands. This was due to the method of taxation: malt was subject to tax (at a rate that climbed substantially between the 1790s and 1822). The licensed distillers, therefore, used more raw grain in an effort to reduce their tax bill.[20]: 119-134

The Highland magistrates, themselves members of the landowning classes, had a lenient attitude to unlicensed distillers—all of whom would be tenants in the local area. They understood that the trade supported the rents paid. Imprisoned tenants would not be able to pay any rent.[20]: 119-134

In 1823, Parliament eased restrictions on licensed distilleries with the Excise Act 1823 (4 Geo. 4. c. 94), while at the same time making it harder for the illegal stills to operate. Magistrates found counsel for the Crown appearing in their courts, so forcing the maximum penalties to be applied, with some cases removed to the Court of Exchequer in Edinburgh for tougher sentences. Highland landowners were now happy to remove tenants who were distillers in clearances on their estates. These changes ushered in the modern era of Scotch production: in 1823 2,232,000 gallons of whisky had duty paid on it; in 1824 this increased to 4,350,000 gallons.[20]: 119–134

A farmer, George Smith, working under landlord the Duke of Gordon, was the first person in Scotland[21] to take out a licence for a distillery under the new act, founding the Glenlivet Distillery in 1824, to make single malt Scotch.[22] Some of the distilleries which started legal operations in the next few years included Bowmore, Strathisla, Balblair, and Glenmorangie; all remain in business today.[18]

Two events helped to increase whisky's popularity. The first was the introduction in 1831 of the column still. Aeneas Coffey patented a refined version of a design originally created by Robert Stein, based on early innovations by Anthony Perrier, for the new type of still[18] which produced whisky much more efficiently than the traditional pot stills.[23] The column still allowed for continuous distillation, without the need for cleaning after each batch was made. This process made manufacturing more affordable by performing the equivalent of multiple distillation steps.[24] The new still dramatically increased production and the resultant whisky was less intense and smoother, making it more popular.[24] Secondly, there was a shortage of wine and brandy in France, significant by 1880, due to phylloxera, a parasitic insect, destroying many vineyards, which led to a surge in demand for whisky. By the 1890s, almost forty new distilleries had opened in Scotland. In a speculative boom, the Edinburgh blenders Pattisons Ltd. came to prominence before spectacularly failing.[25] In the downturn, The Distillers Company were able to buy up other firms' assets.[26] The industry was also affected by disputes about whether grain or blended whisky was worthy of the name, with an adverse decision in North London Police Court in 1905.[27] A Royal Commission on Whisky and other Potable Spirits was appointed in 1906 and reported in 1909 with a victory for the grain distillers and blenders.[28][29] The industry was further affected by World War I, Prohibition in the United States and later, by the Great Depression; many of the companies closed and never re-opened.[18][28][30] Of the 159 distilleries operating in the boom years around 1900, only 15 survived to 1933.[26]

During the 1970s there was a new boom in Scotch whisky production that led to an overproduction in the early 1980s.[31] Starting in 1981 whisky distilleries slashed production by a third and kept it low for a decade. During that time many distilleries closed. Banff, Brora, Coleburn, Convalmore, Dallas Dhu, Glen Albyn, Glenesk, Glen Flagler, Glenlochy, Glen Mhor, Glenugie, Glenury, Millburn, North Port, Port Ellen and St Magdalene were mothballed, shut down or demolished.[32][33]

Since the 2010s, Scotch whisky has entered a new phase of growth with new distilleries like Ardnahoe and Borders opening and older distilleries like Brora, Port Ellen and Rosebank reopening.[34][35]

Regulations and labelling

[edit]Legal definition

[edit]As of 23 November 2009[update], the Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 (SWR) define and regulate the production, labelling, packaging as well as advertising of Scotch whisky in the United Kingdom. They replace previous regulations that focused solely on production, including the Scotch Whisky Act 1988.

Since the previous act focused primarily on production standards, it was repealed and superseded by the 2009 Regulations. The SWR includes broader definitions and requirements for the crafting, bottling, labelling, branding, and selling of "Scotch Whisky". International trade agreements have the effect of making some provisions of the SWR apply in various other countries as well as in the UK. The SWR defines "Scotch whisky" as whisky that:[6][7]

- Is produced at a distillery in Scotland from water and malted barley (to which only whole grains of other cereals may be added) all of which have been:

- Processed at that distillery into a mash

- Converted at that distillery to a fermentable substrate only by endogenous enzyme systems

- Fermented at that distillery only by adding yeast

- Has been distilled at an alcoholic strength by volume of less than 94.8% (190 US proof)

- Is wholly matured in an excise warehouse in Scotland in oak casks of a capacity not exceeding 700 litres (185 US gal; 154 imp gal) for at least three years

- Retains the colour, aroma, and taste of the raw materials used in, and the method of, its production and maturation

- Contains no added substances, other than water and plain (E150A) caramel colouring

- Has a minimum alcoholic strength by volume of 40% (80 US proof)

The Scotch Whisky Association acts as the regulatory body that ensures that Scotch Whisky is produced in accordance with traditional practices, as well as ensuring a sustainable future for the Scotch Whisky industry by promoting sustainable production, global trade, and responsible consumption.[5]

Labelling

[edit]

A Scotch whisky label comprises several elements that indicate aspects of production, age, bottling, and ownership. Some of these elements are regulated by the SWR,[36] and some reflect tradition and marketing.[37] The spelling of the term whisky is often debated by journalists and consumers. Scottish, English, Welsh, Australian and Canadian whiskies use whisky, Irish whiskies use whiskey, while American and other styles vary in their spelling of the term.[38]

The label always features a declaration of the malt or grain whiskies used. A single malt Scotch whisky is one that is entirely produced from malt in one distillery. One may also encounter the term "single cask", signifying the bottling comes entirely from one cask.[38] The term "blended malt" signifies that single malt whisky from different distilleries is blended in the bottle.[39] The Cardhu distillery also began using the term "pure malt" for the same purpose, causing a controversy in the process over clarity in labelling[40][41]—the Glenfiddich distillery was using the term to describe some single malt bottlings. As a result, the Scotch Whisky Association declared that a mixture of single malt whiskies must be labelled a "blended malt". The use of the former terms "vatted malt" and "pure malt" is prohibited. The term "blended malt" is still debated, as some bottlers maintain that consumers confuse the term with "blended Scotch whisky", which contains some proportion of grain whisky.[42]

The brand name featured on the label is usually the same as the distillery name (for example, the Talisker distillery labels its whiskies with the Talisker name). Indeed, the SWR prohibits bottlers from using a distillery name when the whisky was not made there. A bottler's name may also be listed, sometimes independent of the distillery. In addition to requiring that Scotch whisky be distilled in Scotland, the SWR requires that it also be bottled and labelled in Scotland. Labels may also indicate the region of the distillery (for example, Islay or Speyside).[43]

Alcoholic strength is expressed on the label by Alcohol By Volume (ABV) or sometimes simply "Vol".[43] Typically, bottled whisky is between 40% and 46% ABV.[44] Whisky is considerably stronger when first emerging from the cask—normally 60–63% ABV.[43][44] Water is then added to create the desired bottling strength. If the whisky is not diluted before bottling, it can be labelled as cask strength.[44]

A whisky's age may be listed on the bottle providing a guarantee of the youngest whisky used. An age statement on the bottle, in the form of a number, must reflect the age of the youngest whisky used to produce that product. A whisky with an age statement is known as guaranteed age whisky.[45] Scotch whisky without an age statement may, by law, be as young as three years old.[6] In the early 21st century, such "No age statement" whiskies have become more common, as distilleries respond to the depletion of aged stocks caused by improved sales.[46] A label may carry a distillation date or a bottling date. Whisky does not mature once bottled, so if no age statement is provided, one may calculate the age of the whisky if both the distillation date and bottling date are given.[43]

Labels may also carry various declarations of filtration techniques or final maturation processes. A Scotch whisky labelled as "natural" or "non-chill-filtered" has not been through a filtration process during bottling that removes compounds that some consumers see as desirable. Whisky is aged in various types of casks—and often in used port or sherry casks—during distinct portions of the maturation process, and will take on characteristics, flavour, and aromas from such casks. Special casks are sometimes used at the end of the maturation process, and such whiskies may be labelled as "wood finished", "sherry/port finished", and so on.[43]

Economic effects

[edit]Scotland's identity and heritage are deeply intertwined with Scotch Whisky, a cornerstone of the country's economy exported to nearly 180 markets.[5] The Scotch Whisky Association estimated that Scotland's whisky industry supported 40,000 jobs and accounted for £4.37 billion in exports in 2017. Of that total, single malt Scotch accounted for £1.17 billion in exports, a 14% increase over 2016.[47] The drink is exported to nearly 180 markets and, in 2022, its exports were valued at over £6 billion for the first time.

The industry's contribution to the economy of the UK was estimated as £5.5 billion in 2018; the industry provided £3.8 billion in direct GVA (gross value added) to Scotland. Whisky tourism has also become significant and accounts for £68.3 million per year. One factor negatively affected sales, an extra 3.9% duty on spirits imposed by the UK in 2017. (The effect of the 25% increase in tariffs imposed by the U.S. in October 2019 would not be apparent until 2020.) Nonetheless, by year-end 2017, exports had reached a record-breaking amount.[48][49][50][51]

In November 2019, the Association announced that the government of the UK had agreed to consider revising the alcohol taxation system, hopefully producing a new plan that was simplified and "fairer".[52]

Exports in 2018 again increased 7.8% by value, and 3.6% in the number of bottles, in spite of the duty imposed in 2017; exports grew to a record level, £4.7 billion.[53] The US imported Scotch whisky with a value of just over £1 billion while the European Union was the second-largest importer, taking 30% of global value. This was a boom year with a record high in exports, but the Scotch Whisky Association expressed concern for the future, particularly "the challenges posed by Brexit and by tensions in the global trading system".[54]

Scotch whisky tourism has developed around the industry, with distilleries being the third most visited attraction in Scotland; roughly 2 million visits were recorded in 2018. Some 68 distilleries operate visitors' centres in Scotland and another eight accept visits by appointment. Hotels, restaurants, and other facilities are also impacted by the tourism phenomenon. Tourism has had an especially visible impact on the economy in some remote rural areas, according to Fiona Hyslop MSP, Cabinet Secretary for Culture, Tourism and External Affairs. "The Scottish Government is committed to working with partners like the Scotch Whisky Association to increase our tourism offer and encourage more people to visit our distilleries," the Secretary said.[55][56]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, exports of many food and drink products from the UK declined significantly,[57] and that included Scotch whisky. Distillers were required to close for some time and the hospitality industry worldwide experienced a major slump.[58] According to news reports in February 2021, the Scotch whisky sector had experienced £1.1 billion in lost sales. Exports to the US were also affected by the 25% tariff that had been imposed. Scotch whisky exports to the US during 2020 "fell by 32%" from the previous year. Worldwide exports fell in 70% of Scotch whisky's global markets.[59] A BBC News headline on 12 February 2021 summarized the situation: "Scotch whisky exports slump to 'lowest in a decade'".[60]

Ownership of distilleries

[edit]A 2016 report stated that only 20% of the whisky was made by companies owned in Scotland. Distilleries owned by Diageo, a London-based company, produce 40% of all Scotch whisky, with over 24 brands, such as Johnnie Walker, J&B and Vat 69. Another 20% of the product is made by distillers owned by Pernod Ricard of France, including brands such as Ballantine's, Chivas Regal and Glenlivet . There are also 12% made by smaller distillers that are owned by foreign companies, such as Cutty Sark and Label 5 owned by La Martiniquaise of France, Dewar's and William Lawson's owned by Bacardi Limited of Bermuda and BenRiach whose parent is the Brown–Forman Corporation based in Kentucky, United States. Nonetheless, Scotch whisky is produced according to the current regulations, as to ageing, production, and so on, ensuring that it remains Scottish.[18]

Independents owned by Scots companies make a substantial amount of Scotch whisky, with the largest, William Grant & Sons, producing 8%, or about 7.6 million cases per year. Its brands include Balvenie, Glenfiddich, and Grant's.[61] Glenfiddich is the best-selling single malt Scotch in the world.[62] Roughly 14 million bottles of Glenfiddich are sold annually.[61]

Independent bottlers

[edit]Most malt distilleries sell a significant amount of whisky by the cask for blending, and sometimes to private buyers as well. Whisky from such casks is sometimes bottled as a single malt by independent bottling firms such as Duncan Taylor, Master of Malt,[63] Gordon & MacPhail, Cadenhead's, The Scotch Malt Whisky Society, Murray McDavid, Berry Bros. & Rudd, Douglas Laing, Adelphi and others.[64] These are usually labelled with the distillery's name, but not using the distillery's trademarked logos or typefaces. An "official bottling" (or "proprietary bottling"), by comparison, is from the distillery (or its owner). Many independent bottlings are from single casks, and they may sometimes be very different from an official bottling.[64]

For a variety of reasons, some independent bottlers do not identify which distillery produced the whisky in the bottle. Mostly this will be at the request of the whisky distiller as they are unable to regulate the quality of the whisky sold. Some distilleries, to prevent third-party bottlers from naming them on the bottle, add a small amount of whisky from a different distillery, a technique called 'tea-spooning' which then precludes the sale of the whisky as from a specific distillery, or as a single malt; the addition of any whisky from a second distillery is by regulation a blended malt (which will also allow it to be exported in bulk form, unlike single malts which may only be exported bottled ready for sale).[65] Instead the bottler may identify only the general geographical area of the source, or simply market the product using their own brand name without identifying their source. This may, in some cases, give the independent bottling company the flexibility to purchase from multiple distillers without changing their labels.

Types

[edit]

There are two basic types of Scotch whisky, from which all blends are made:

- Single malt Scotch whisky must have been distilled at a single distillery as a batch process using a pot still distillation process and made from a mash of 100% malted barley. Single malt means that the whisky has not been blended elsewhere with whisky from other distilleries. A single malt Scotch must be distilled in Scotland and matured in oak casks in Scotland for at least three years, although most single malts are matured longer and also must be bottled in Scotland.[66][67]

- Single grain Scotch whisky is a Scotch whisky distilled at a single distillery but, in addition to water and malted barley, may involve whole grains of other malted or unmalted cereals. Grain whisky can be distilled continuously in continuous stills or column stills.[68] Single grain whisky can essentially be seen as any spirit from one distillery which qualifies as whisky but does not qualify as malt whisky. "Single grain" does not mean that only a single type of grain was used to produce the whisky; rather, the adjective "single" refers only to the use of a single distillery (and making a "single grain" generally requires using a mixture of grains, as barley is a type of grain and some malted barley must be used in all Scotch whisky - although a single grain whisky can be made entirely from malted barley and continuously distilled).

Excluded from the definition of "single malt Scotch whisky" or "single grain Scotch whisky" is any spirit that qualifies as a blended Scotch whisky. This exclusion is to ensure that a blended Scotch whisky produced from single malt(s) and single grain(s) distilled at the same distillery does not also qualify as single malt Scotch whisky or single grain Scotch whisky. Nearly 90% of the bottles of Scotch sold per year are blended whiskies.[67]

Three types of blends are defined for Scotch whisky:

- Blended malt Scotch whisky means a blend of two or more single malt Scotch whiskies from different distilleries.

- Blended grain Scotch whisky means a blend of two or more single grain Scotch whiskies from different distilleries.

- Blended Scotch whisky means a blend of one or more single malt Scotch whiskies with one or more single grain Scotch whiskies.

The five Scotch whisky definitions are structured in such a way that the categories are mutually exclusive. The 2009 regulations changed the formal definition of blended Scotch whisky to achieve this result, but in a way that reflected traditional and current practice: before the 2009 SWR, any combination of Scotch whiskies qualified as a blended Scotch whisky, including for example a blend of single malt Scotch whiskies.

As was the case under the Scotch Whisky Act 1988, regulation 5 of the SWR 2009 stipulates that the only whisky that may be manufactured in Scotland is Scotch whisky. The definition of manufacture is "keeping for the purpose of maturation; and keeping, or using, for the purpose of blending, except for domestic blending for domestic consumption". This provision prevents the existence of two "grades" of whisky originating from Scotland, one "Scotch whisky" and the other, a "whisky product of Scotland" that complies with the generic EU standard for whisky. According to the Scotch Whisky Association, allowing non-Scotch whisky production in Scotland would make it difficult to protect Scotch whisky as a distinctive product.[7] The SWR regulation also states that no additives may be used except for plain (E150A) caramel colouring.[69]

Single malt

[edit]To qualify for this category the Scotch whisky must be made in one distillery, in a pot still by batch distillation, using only water and malted barley.[70] As with any other Scotch whisky, the Scotch Whisky Regulations of 2009 also require single malt Scotch to be made completely and bottled in Scotland and aged for at least three years. Most are aged longer.[71][67]

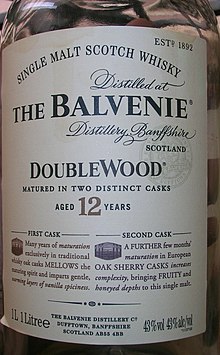

Another term is sometimes seen, called "double wood" or "triple wood", sometimes incorrectly referred to as "double malt" or "triple malt". These indicate that the whisky was aged in two or three types of casks. Hence, if the whisky otherwise meets the criteria of single malt, it still falls into the single malt category even if more than one type of cask was used for ageing.[69] Examples include The Balvenie 12 Year DoubleWood and Laphroaig Triple Wood.

Another nuance is that Lowland Scotch malts use a triple distillation just like Irish whiskey, breaking away from the general rule that all Scotch is double distilled.[72]

Single grain

[edit]Single grain whisky is made with water and malted barley but the distillery then adds other grains or cereals, wheat, corn, or rye, for example. From that moment on, it can no longer be called single malt. This type of product must be from a single distillery and is often used in making blended Scotch.[69] Single grain whiskies are usually not distilled in pot stills but with column stills.[73]

Blended malt

[edit]Blended malt whisky, formerly called vatted malt or pure malt (terms that are now prohibited in the SWR 2009), is one of the least common types of Scotch: a blend of single malts from more than one distillery (possibly with differing ages).

Blended malts contain only single malt whiskies from two or more distilleries.[69] This type must contain no grain whiskies and is distinguished by the absence of the word "single" on the bottle. The age of the vat is that of the youngest of the original ingredients. For example, a blended malt marked "8 years old" may include older whiskies, with the youngest constituent being eight years old. Johnnie Walker Green Label and Monkey Shoulder are examples of blended malt whisky. Starting from November 2011, no Scotch whisky could be labelled as a vatted malt or pure malt, the SWR requiring them to be labelled blended malt instead.[74]

Blended grain

[edit]The term blended grain Scotch refers to whisky that contains at least two single grain Scotch whiskies from at least two distilleries, combined to create one batch of the product.[75]

Blended

[edit]

Blended Scotch whisky constitutes about 90% of the whisky produced in Scotland.[76] Blended Scotch whiskies contain both malt whisky and grain whisky. Producers combine the various malts and grain whiskies to produce a consistent brand style. Notable blended Scotch whisky brands include Ballantine's, Bell's, Chivas Regal, Cutty Sark, Dewar's, Grant's, J&B, Johnnie Walker, Teacher's Highland Cream, The Famous Grouse, Vat 69, Whyte and Mackay and William Lawson's. Most Blended Scotch Whiskies are made from the produce of at least two distilleries as the majority of distilleries produce only malt or grain whiskies; however a few distilleries such as Loch Lomond produce both malt and grain whisky at the same site.

Regions

[edit]

Scotland was traditionally divided into four whisky regions: Campbeltown, The Highlands, The Isle of Islay and The Lowlands.[77] Due to the large number of distilleries found there, the Speyside area became the fifth, recognised by the Scotch Whisky Association (SWA) as a distinct region in 2014.[78] The whisky-producing islands other than Islay are not recognised as a distinct region by the SWA, which groups them into the Highlands region.[78]

- Campbeltown, a small western coastal town, was once home to over 30 distilleries but now has only three in operation: Glen Scotia, Glengyle, and Springbank. Characteristics vary, but in general, the whiskies are described as "fruity, peaty, sweet, smoky" by the national tourist board; another source published by a marketing company also mentions the "flavor of wet dog, also called wet wool".[79][80]

- The Highlands: The Highlands is by far the largest region in Scotland both in area and in whisky production. This massive area has over 30 distilleries on the mainland. Region characteristics: "fruity, sweet, spicy, malty", according to the national tourist board.[81][80] When the Islands sub-region is included, the total number of distilleries is 47.[81]

- Some Highland distilleries: Fettercairn, Aberfeldy, Edradour, Balblair, Ben Nevis, Dalmore, Glen Ord, Glenmorangie, Oban, Glendronach, Old Pulteney, Tullibardine and Tomatin.

- The Islands, an unrecognised sub-region of the Highlands, includes all of the whisky-producing islands other than Islay: Arran, Jura, Mull, Orkney, Raasay and Skye: with their respective distilleries: Arran, Jura, Highland Park, Scapa, Raasay, Talisker and Tobermory.[82][83]

- Islay /ˈaɪlə/: has nine producing distilleries:[84] Ardbeg, Ardnahoe (the most recent), Bowmore (the oldest, having opened in 1779), Bruichladdich, Bunnahabhain, Caol Ila, Kilchoman, Lagavulin, and Laphroaig. Region Characteristics: distilleries in the south make whisky which is "medium-bodied ... saturated with peat-smoke, brine and iodine" because they use malt that is heavy with peat as well as peaty water. Whisky from the northern area is milder because it is made using spring water for a "lighter flavoured, mossy (rather than peaty), with some seaweed, some nuts..." characteristic.[85] The national tourist board website says that the single malts from Islay vary by distillery, from "robust and smoky" to "lighter and sweeter".[86]

- The Lowlands: According to Visit Scotland, the website of the national tourist board, this district covers "much of the Central Belt and the South of Scotland including Edinburgh & The Lothians, Glasgow & The Clyde Valley, the Kingdom of Fife, Ayrshire, Dumfries & Galloway and the Scottish Borders".[87]

- There were 18 Lowlands distilleries in the region as of 2019[update], according to the website of the national tourist board, including some that opened quite recently.[87] These include well-known companies such as Annandale, Auchentoshan, Bladnoch, Glenkinchie, and Ailsa Bay in the site of the Girvan distillery as well as Daftmill, Eden Mill, Kingsbarns and Rosebank.[78][88][89][90][91] Region characteristics: soft and smooth, consisting of a floral nose with a sweet finish.[92] Single malts from this area tend to be "lighter, sweet and [with] floral tones".[87]

- Speyside: Speyside gets its name from the River Spey, which cuts through this region and provides water to many of the distilleries.

- Encompassing the area surrounding the River Spey in north-east Scotland, once considered part of the Highlands, the region has approximately 50 distilleries within its geographic boundaries and has officially been recognised as a region, distinct from the Highlands, since 2014. According to the national tourist board, Speyside includes the area between the Highlands to the west and Aberdeenshire in the east, extending north from the Cairngorms National Park.[93] According to one source, the top five in 2019 were Aberlour, Balvenie, Glenfarclas, Glenfiddich, and The Macallan. Region characteristics: vary greatly from "rich and textured to fragrantly floral"; in general, "sweet, "caramel", "fruity" and "spicy", according to the national tourist board.[93] According to a marketing agency, the single malts from Speyside are known for a smokiness and complexity.[80]

- It has the largest number of distilleries of any region, which includes: Aberlour, Balvenie, Cardhu, Cragganmore, Dalwhinnie, Glenfarclas, Glenglassaugh, Glenfiddich, Speyburn, The Glenlivet, The Glenrothes and The Macallan.[7]

- Due to the way that the regions are specified, Speyside is wholly within the Highland region and thus whiskies produced in Speyside may legally be described as coming from either region; for example Glenfarclas generally labels their whiskies as Highland Single Malts.[94]

Although only five regions are specified, any Scottish locale may be used to describe a whisky if it is distilled entirely within that place; for example, a single malt whisky distilled on Orkney could be described as Orkney Single Malt Scotch Whisky[7] instead of as an Island whisky.

Sensory characteristics

[edit]Flavour and aroma

[edit]Dozens of compounds contribute to Scotch whisky flavour and aroma characteristics, including volatile alcohol congeners (also called higher oils) formed during fermentation, such as acetaldehyde, methanol, ethyl acetate, n-propanol and isobutanol.[95] Other flavour and aroma compounds include vanillic acid, syringic acid, vanillin, syringaldehyde, furfural, phenyl ethanol and acetic acid.[95][96] One analysis established 13 distinct flavour characteristics dependent on individual compounds, including sour, sweet, grainy and floral as major flavour perceptions.[96]

Some distilleries use a peat fire to dry the barley for some of their products before grinding it and making the mash.[67] Peat smoke contributes phenolic compounds, such as guaiacol,[96] that give aromas similar to smoke. The Maillard browning process of the residual sugars in the mashing process, particularly through formation of 2-furanmethanol and pyrazines imparting nutty or cereal characteristics contributes to the baked bread notes in the flavour and aroma profile.[97] Maturation during multi-year casking[96] in oak barrels mostly previously used for bourbon whiskey, Sherry, Wines, Fortified Wine, (including Port and Madeira) Rum and other spirit production, has the largest impact on the flavour of the whisky. Some distilleries use Virgin Oak casks as used casks are becoming increasingly harder to source (particularly authentic sherry casks due to the downturn in sherry consumption plus the laws introduced in 1986 regarding bottling Spanish wines exclusively in Spain)[98]

Screening for potential adulteration

[edit]Refilling and fabrication or tampering of branded Scotch whiskies are types of Scotch whisky adulteration that diminishes brand integrity, consumer confidence, and profitability in the Scotch industry.[95] Deviation from normal concentrations of major constituents, such as alcohol congeners, provides a precise, quantitative method for determining authenticity of Scotch whiskies.[95] Over 100 compounds can be detected during counterfeit analysis, including phenolics and terpenes which may vary in concentration by different geographic origins, the barley used in the fermentation mash, or the oak cask used during ageing.[99] Typical high-throughput instruments used in counterfeit detection are liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry.[95][99]

Gallery

[edit]-

Scotch Whisky Heritage Center

-

The Scotch whisky experience

-

Macallan Distillery production hall

-

Bowmore Distillery

-

Glenlivet Distillery

See also

[edit]- Outline of whisky

- List of whisky brands

- List of whisky distilleries in Scotland

- Scotch Whisky Research Institute

- New world whisky

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "whisky". Scottish National Dictionary. Retrieved 13 January 2021 – via Dictionary of the Scots Language.

- ^ a b Exchequer Rolls of Scotland 1494–95. Vol. 10. p. 487.

Et per liberacionem factam fratri Johanni Cor per perceptum compotorum rotulatoris, ut asserit, de mandato domini regis ad faciendum aquavite infra hoc compotum viij bolle brasii.

- ^ MacLean 2010, p. 10.

- ^ "Facts & Figures". The Scotch Whisky Association. Retrieved 20 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Jewell, Catherine (April 2023). "Scotch Whisky Sees IP, Diversity and Inclusion as Keys To its Longer-term Sustainability". WIPO Magazine.

- ^ a b c d Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Scotch Whisky Association 2009.

- ^ "What is the alcoholic strength of Scotch Whisky?". The Scotch Whisky Association. 1 December 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ^ Simpson, John A.; Weiner, Edmund S.C., eds. (1989). "dram, n.". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861186-8. OCLC 50959346. Retrieved 2 July 2012. Earlier version first published in New English Dictionary, 1897.

- ^ "Scotch Whisky FAQs". Scotch Whisky Association. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "whiskey". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 16 May 2023.

- ^ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland. Vol. 1. Edinburgh. December 1497. pp. ccxiii–iv, 373.

Item, to the barbour that brocht acqua vitae to the King in Dundee, by the King's command, xxxi shillings.

- ^ "Whisky or Whiskey". Master of Malt. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ "History". Scotch Whisky Association. Retrieved 16 July 2012.

- ^ "The Still in context: a list of early references related to aquavite in Scotland". Aberdeen Registers. 2019. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "Aberdeen Registers Online: 1398-1511". University of Aberdeen. 2019.

entry reference ARO-8-0466-02

- ^ "Famous whisky drinkers: King James IV | Scotch Whisky". scotchwhisky.com.

- ^ a b c d e "A Comprehensive Yet Concise History of Scotch Whisky". Bespoke Unit. 17 May 2018. Retrieved 25 December 2019.

- ^ "The Origins and History of Whisky | The Scotch Whisky Experience". www.scotchwhiskyexperience.co.uk. Retrieved 1 September 2021.

- ^ a b c Devine, T M (1994). Clanship to Crofters' War: The social transformation of the Scottish Highlands (2013 ed.). Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-9076-9.

- ^ "Glenlivet Single Malt Scotch Whisky | The Whisky Shop". www.whiskyshop.com.

- ^ "The Story". The Glenlivet.

- ^ The Oxford Encyclopedia of Economic History. Oxford University Press. 2003. p. 96. ISBN 978-0-19-510507-0. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ a b "The Difference Between Pot Versus Column Stills, Explained". VinePair. 5 October 2018.

- ^ Murphy, Sean (21 September 2023). "The Pattison Bros: The men who nearly brought down the Scotch whisky industry". The Scotsman. Retrieved 7 January 2025.

- ^ a b Vorel, Jim (22 May 2020). "How Two Brothers Managed to Almost Destroy the 20th Century Scotch Whisky Industry". Paste Magazine. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Bruce-Gardyne, Tom (16 April 2000). "Peter the great". Whisky Magazine. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ a b Storrie, Margaret (1962). "The Scotch Whisky Industry". Transactions and Papers (Institute of British Geographers) (31): 102. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ "The Royal Commission On Whisky And Other Potable Spirits". British Medical Journal. 2 (2537): 399–404. 14 August 1909. Retrieved 8 January 2025.

- ^ Ranahan, Jared (12 July 2019). "How Phylloxera Jumpstarted the Modern Whiskey Industry".

- ^ "Scotch on a Rising Tide | WhiskyInvestDirect". www.whiskyinvestdirect.com. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Is a second 'whisky loch' brewing? | Scotch Whisky". scotchwhisky.com. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "What We Lost in the Whisky Loch". whiskyadvocate.com. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Scotch whisky distilleries to open in 2018 | Scotch Whisky". scotchwhisky.com. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ "Scotch whisky distilleries to open in 2019 | Scotch Whisky". scotchwhisky.com. Retrieved 4 March 2023.

- ^ MacLean 2010, p. 20.

- ^ MacLean 2010, p. 23.

- ^ a b Jackson 2010, p. 22.

- ^ Jackson 2010, p. 23.

- ^ "Whisky branding deal reached". BBC News. 4 December 2003. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ Tran, Mark (4 December 2003). "Whisky industry settles on strict malt definitions". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 March 2014.

- ^ Jackson 2010, pp. 419–420.

- ^ a b c d e MacLean 2010, p. 21.

- ^ a b c Jackson 2010, p. 25.

- ^ Hansell 2010.

- ^ Dickie, Mure (9 December 2013). "Hopes soar for spirited revival". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ^ Sparks, Cator (10 September 2018). "Scotland's Next Wave of Whisky Distilleries". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "Scotch Whisky Economic Impact Report 2018". Scotch Whisky Association. 30 April 2019. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023.

- ^ "Whisky Tourism Facts and Insights" (PDF). VisitScotland. 2018 [March 2015]. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 April 2022.

- ^ Stewart, Heather; O'Carroll, Lisa (7 October 2019). "PM urged to confront Trump over US tariffs on scotch whisky". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 October 2023.

- ^ Inman, Phillip (12 October 2017). "Cut duty on Scotch whisky to raise industry spirits, say distillers". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 5 April 2023.

- ^ "SWA response duty system review". Scotch Whisky Association. 7 November 2019. Archived from the original on 5 June 2023.

- ^ "Scotch Whisky Exports rise in 2018". Scotch Whisky Association. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 6 April 2023.

- ^ "HMRC data shows Scotch exports hit record high in 2018". BBC News. 12 February 2019. Archived from the original on 20 January 2024.

- ^ Almeida, Andre de (21 June 2019). "Record numbers of visitors for Scotch Whisky Distilleries". Inside the Cask. Archived from the original on 8 November 2023.

- ^ "Scotch whisky tourism at all-time high | Scotch Whisky". scotchwhisky.com.

- ^ "Data shows collapse of UK food and drink exports post-Brexit". TheGuardian.com. 22 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Scotland's whisky islands are dealing with a major Covid hangover". CNN. 10 October 2020. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "COVID costs Scotch whisky exports £1.1 billion in lost sales". 12 February 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Scotch whisky exports slump to 'lowest in a decade'". BBC News. 12 February 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ a b "Top 15 Scotch whisky companies". www.whiskyinvestdirect.com. WhiskyInvestDirect.

- ^ Koutsakis, George. "World's Bestselling Single Malt Whisky Undergoes Risky Change". Forbes.

- ^ "Buy Whisky Online | Single Malt Whisky & More". Master of Malt.

- ^ a b "Independent Bottlers - scotchwhisky.net". www.scotchwhisky.net.

- ^ "Independence Day". The Really Good Whisky Company. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "How Single Malt Whisky Is Made - Whisky.com". www.whisky.com.

- ^ a b c d "Scotch Whisky FAQs". Scotch Whisky Association.

- ^ "How is Whisky Made?". 2 October 2019.

- ^ a b c d Shapira, J. A. (25 May 2018). "The Scotch Whisky Guide". www.gentlemansgazette.com.

- ^ "The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 December 2019. Retrieved 29 December 2019.

- ^ "How Single Malt Whisky is made - Whisky.com". www.whisky.com.

- ^ "The Difference Between Scotch and Whiskey". 21 December 2019.

- ^ "What exactly makes a scotch 'single malt', 'single grain' or a 'blend'?". Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Scotch Whisky Association 2009, Chapter 11.

- ^ Smith, Gavin D. (2018). MicroDistillers' Handbook. Paragraph Publishing. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-9998408-0-8.

- ^ "Statistical Report" (PDF). scotch-whisky.org. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 January 2012. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009 – Chapter 8 section 1

- ^ a b c "Whisky Regions & Tours". Scotch Whisky Association. Archived from the original on 26 July 2018. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Campbeltown Whisky Distilleries – Map & Tours". VisitScotland.

- ^ a b c "All The Scotch Distilleries, locations and Flavors". The Scotch Advocate. Napier Marketing Group. Archived from the original on 17 December 2019.

- ^ a b "Highland Distilleries – Whisky Tours, Tastings & Map". VisitScotland.

- ^ "Scotch Whisky Regions". Scotch Whisky Association.

- ^ Powell, Tom (31 July 2018). "The beginner's guide to scotch whisky". Foodism.

- ^ "Islay Malt Whisky and Islay Whisky Distilleries Map". www.islayinfo.com. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- ^ "Islay Malt Whisky and Islay Whisky Distilleries Map". www.islayinfo.com.

- ^ "Islay Distilleries – Whisky Tours, Tastings & Map". VisitScotland.

- ^ a b c "Lowland Whisky – Map & Distillery Tours Near Edinburgh & Glasgow". VisitScotland.

- ^ "Eden Mill—Scotch Whisky". Scotchwhisky.com. Retrieved 9 September 2018.

- ^ "Lowland > Daftmill". Whiskies of Scotland. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 3 December 2013.

- ^ "Spirited revival for third distillery". 10 October 2017. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Rosebank distillery set to reopen in 2020 | Scotch Whisky". scotchwhisky.com. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Your Cheat Sheet to Scottish Whisky Regions". Flaviar. 14 September 2016. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ^ a b "Speyside Distilleries – Whisky Tours, Tastings & Map". VisitScotland.

- ^ "Highland vs Speyside – a tale of two regions – The Whisky Exchange Whisky Blog — The Whisky Exchange Whisky Blog". 18 August 2017. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Smith, Barry L.; Hughes, David M.; Badu-Tawiah, Abraham K.; Eccles, Rebecca; Goodall, Ian; Maher, Simon (29 May 2019). "Rapid Scotch whisky analysis and authentication using desorption atmospheric pressure chemical ionisation mass spectrometry". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 7994. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9.7994S. doi:10.1038/s41598-019-44456-0. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6541643. PMID 31142757.

- ^ a b c d Lee, K.-Y. Monica; Paterson, Alistair; Piggott, John R.; Richardson, Graeme D. (2000). "Perception of whisky flavour reference compounds by Scottish distillers". Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 106 (4): 203–208. doi:10.1002/j.2050-0416.2000.tb00058.x. ISSN 0046-9750.

- ^ Boothroyd, Emily; Linforth, Robert S. T.; Jack, Frances; Cook, David J. (2 December 2013). "Origins of the perceived nutty character of new-make malt whisky spirit". Journal of the Institute of Brewing. 120 (1): 16–22. doi:10.1002/jib.103. ISSN 0046-9750.

- ^ "Different Types of Whisky Casks and Their Impact on the Whisky..." The Really Good Whisky Company. 4 July 2021. Retrieved 4 July 2021.

- ^ a b Vosloo, Nicola (21 October 2015). "Identifying whiskey counterfeits". Food Quality and Safety. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

Books

[edit]- Bender, David A (2005). A Dictionary of Food and Nutrition. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860961-2.

- Hansell, John (28 June 2010). "What Does a Whisky's Age Really Mean?". Whisky Advocate. Retrieved 17 March 2012.

- Jackson, Michael (2010). Michael Jackson's Complete Guide to Single Malt Scotch (6th ed.). DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7566-5898-4.

- MacLean, Charles (2010). Whiskypedia: A Compendium of Scottish Whisky. Skyhorse Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61608-076-1.

- MacLean, Charles, ed. (2009). World Whiskey: A Nation-by-Nation Guide to the Best. DK Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7566-5443-6.

- "The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009: Guidance for Producers and Bottlers" (PDF). Scotch Whisky Association. 2 December 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 June 2017. Retrieved 24 September 2012.

- "The Scotch Whisky Regulations 2009". UK Parliament. 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2012.

Further reading

[edit]- Broom, Dave (1998). Whiskey: A Connoisseur's Guide. London. Carleton Books Limited. ISBN 1-85868-706-3.

- Broom, Dave (2000). Handbook of Whisky. London. Hamlyn. ISBN 0-600-59846-2.

- Lockhart, Sir Robert (2011). Scotch: The Whisky of Scotland in Fact and Story (8th ed.). Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 978-1-906476-22-9.

- Buxton, Ian; Hughes, Paul S. (2014). The Science and Commerce of Whisky. Cambridge, England: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 978-1-84973-150-8.

- Erskine, Kevin (2006). The Instant Expert's Guide to Single Malt Scotch – Second Edition. Richmond, VA. Doceon Press. ISBN 0-9771991-1-8.

- Henley, Jon (15 April 2011). "How the world fell in love with [Scotch] whisky". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 March 2014.

- MacLean, Charles (2003). Scotch Whisky: A Liquid History. Cassell Illustrated. ISBN 1-84403-078-4.

- McDougall, John; Smith, Gavin D. (2000). Wort, Worms & Washbacks: Memoirs from the Stillhouse. Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 978-1-897784-65-5.

- Mitchell, Ian R. (5 March 2015). Wee Scotch Whisky Tales. Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 978-1-906476-28-1.

- Smith, Gavin D. (2013). Stillhouse Stories – Tunroom Tales. Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 978-1-906000-15-8.

- Townsend, Brian (2015). Scotch Missed: The Original Guide to the Lost Distilleries of Scotland (4th ed.). Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 978-1-906000-82-0.

- Wilson, Neil (2003). The Island Whisky Trail: An Illustrated Guide to The Hebridean Whisky Distilleries. Glasgow: Angels' Share (Neil Wilson Publishing). ISBN 1903238498.

- Wishart, David (2006). Whisky classified : choosing single malts by flavour (Revised ed.). London: Pavilion. ISBN 1-86205-716-8. OCLC 148252141.