Piedmont

Piedmont

Piemonte (Italian) Piemont (Piedmontese) Piemont (Occitan) Piemont (Arpitan) | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Anthem: Ël Drapò a deuv vive | |

| |

| Coordinates: 45°04′N 7°42′E / 45.067°N 7.700°E | |

| Country | Italy |

| Capital | Turin |

| Government | |

| • President | Alberto Cirio (FI) |

| Area | |

• Total | 25,402 km2 (9,808 sq mi) |

| Population (31 January 2021) | |

• Total | 4,269,714 |

| • Density | 170/km2 (440/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | English: Piedmontese Italian: Piemontese |

| GDP | |

| • Total | €136.007 billion (2021) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| ISO 3166 code | IT-21 |

| HDI (2021) | 0.901[2] very high · 10th of 21 |

| NUTS Region | ITC1 |

| Website | www |

Piedmont (/ˈpiːdmɒnt/ PEED-mont; Italian: Piemonte [pjeˈmonte]; Piedmontese: Piemont [pjeˈmʊŋt]),[a] located in northwest Italy, is one of the 20 regions of Italy.[3] It borders the Liguria region to the south, the Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna regions to the east, and the Aosta Valley region to the northwest. Piedmont also borders Switzerland to the north and France to the west.

Piedmont has an area of 25,402 km2 (9,808 sq mi), making it the second-largest region of Italy after Sicily. As of 31 January 2021, the population was 4,269,714. The capital of Piedmont is Turin, which was also the capital of the Kingdom of Italy from 1861 to 1865.

Toponymy

[edit]The French Piedmont, the Italian Piemonte, and other variant cognates come from the medieval Latin Pedemontium or Pedemontis, i.e. ad pedem montium, meaning "at the foot of the mountains" (referring to the Alps), attested in documents from the end of the 12th century.[4]

Geography

[edit]

Piedmont is surrounded on three sides by the Alps, including Monviso, where the river Po rises, and Monte Rosa. It borders France (Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes and Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur), Switzerland (Ticino and Valais), and the Italian regions of Lombardy, Liguria, Aosta Valley, and for a very small part with Emilia Romagna. The geography of Piedmont is 43.3% mountainous, along with extensive areas of hills (30.3%) and plains (26.4%).

Piedmont is the second largest of Italy's 20 regions, after Sicily. It is broadly coincident with the upper part of the drainage basin of the river Po, which rises from the slopes of Monviso in the west of the region and is Italy's largest river. The Po drains the semicircle formed by the Alps and Apennines, which surround the region on three sides.

The countryside is very diverse: from the rugged peaks of the massifs of Monte Rosa and Gran Paradiso to the damp rice paddies of Vercelli and Novara, from the gentle hillsides of the Langhe, Roero, and Montferrat to the plains. 7.6% of the entire territory is considered protected area. There are 56 different national or regional parks; one of the most famous is the Gran Paradiso National Park, between Piedmont and the Aosta Valley.

Piedmont has a typically temperate climate, which on the Alps becomes progressively temperate-cold and colder as it climbs to altitude. In areas located at low altitudes, winters are relatively cold but not very rainy and often sunny, with the possibility of snowfall, sometimes abundant. Snowfall, on the other hand, is less frequent and occasional in the northeast areas. Summers are hot with local possibilities of strong thunderstorms.[5]

Major towns and cities

[edit]| Population rank | City name | Population (ab) |

Surface (km2) |

Density (ab/km2) |

Altitude (m s.l.m.) |

Province or metropolitan city |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Turin | 875,698 | 130.17 | 6,786 | 239 | TO |

| 2 | Novara | 104,411 | 103.05 | 1,013 | 162 | NO |

| 3 | Alessandria | 93,884 | 203.97 | 460 | 95 | AL |

| 4 | Asti | 76,424 | 151.82 | 504 | 123 | AT |

| 5 | Moncalieri | 57,060 | 47.63 | 1,197 | 260 | TO |

| 6 | Cuneo | 56,116 | 119.88 | 468 | 534 | CN |

| 7 | Collegno | 49,940 | 18.12 | 2,756 | 302 | TO |

| 8 | Rivoli | 48,819 | 29.52 | 1,653 | 390 | TO |

| 9 | Nichelino | 48,182 | 20.64 | 2,334 | 229 | TO |

| 10 | Settimo Torinese | 47,704 | 32.37 | 1,473 | 207 | TO |

Below are listed other towns of Piedmont with more than 20,000 inhabitants sorted by population.

| Population rank | City Name | Population (ab) |

Surface (km2) |

Density (ab/km2) |

Altitude (m s.l.m.) |

Province or metropolitan city |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | Vercelli | 46,808 | 79.85 | 586 | 130 | VC |

| 12 | Biella | 44,860 | 46.68 | 961 | 417 | BI |

| 13 | Grugliasco | 37,906 | 13.12 | 2,889 | 293 | TO |

| 14 | Chieri | 36,778 | 54.30 | 677 | 305 | TO |

| 15 | Pinerolo | 35,778 | 50.28 | 711 | 376 | TO |

| 16 | Casale Monferrato | 34,565 | 86.32 | 400 | 116 | AL |

| 17 | Venaria Reale | 34,248 | 20.29 | 1,687 | 262 | TO |

| 18 | Alba | 31,419 | 54.01 | 581 | 172 | CN |

| 19 | Verbania | 30,933 | 36.62 | 844 | 197 | VB |

| 20 | Bra | 29,705 | 59.61 | 498 | 285 | CN |

| 21 | Carmagnola | 29,052 | 96.38 | 301 | 240 | TO |

| 22 | Novi Ligure | 28,257 | 54.22 | 521 | 199 | AL |

| 23 | Tortona | 27,575 | 99.29 | 278 | 122 | AL |

| 24 | Chivasso | 26,704 | 51.31 | 520 | 183 | TO |

| 25 | Fossano | 24,743 | 130.72 | 189 | 375 | CN |

| 26 | Ivrea | 23,598 | 30.19 | 781 | 253 | TO |

| 27 | Orbassano | 23,240 | 22.05 | 1,053 | 273 | TO |

| 28 | Mondovì | 22,592 | 87.25 | 258 | 395 | CN |

| 29 | Borgomanero | 21,709 | 32.36 | 670 | 307 | NO |

| 30 | Savigliano | 21,306 | 110.73 | 192 | 321 | CN |

| 31 | Trecate | 20,329 | 38.38 | 529 | 136 | NO |

| 32 | Acqui Terme | 20,054 | 33.30 | 602 | 156 | AL |

History

[edit]

Piedmont was inhabited in early historic times by Celtic-Ligurian tribes such as the Taurini and the Salassi. They were later subdued by the Romans (c. 220 BC), who founded several colonies there including Augusta Taurinorum (Turin) and Eporedia (Ivrea). After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, the region was successively invaded by the Burgundians, the Ostrogoths (5th century), East Romans, Lombards (6th century), and Franks (773).

In the 9th–10th centuries there were further incursions by the Magyars, Saracens and Muslim Moors.[6] At the time Piedmont, as part of the Kingdom of Italy within the Holy Roman Empire, was subdivided into several marches and counties. In 1046, Otto of Savoy added Piedmont to the County of Savoy, with a capital at Chambéry (now in France). Other areas remained independent, such as the powerful comuni (municipalities) of Asti and Alessandria and the marquisates of Saluzzo and Montferrat. The County of Savoy became the Duchy of Savoy in 1416, and Duke Emanuele Filiberto moved the seat to Turin in 1563. In 1720, the Duke of Savoy became King of Sardinia, founding what evolved into the Kingdom of Sardinia and increasing Turin's importance as a European capital.

The Republic of Alba was created in 1796 as a French client republic in Piedmont. A new client republic, the Piedmontese Republic, existed between 1798 and 1799 before it was reoccupied by Austrian and Russian troops. In June 1800 a third client republic, the Subalpine Republic, was established in Piedmont. It fell under full French control in 1801 and it was annexed by France in September 1802. In the Congress of Vienna, the Kingdom of Sardinia was restored and furthermore received the Republic of Genoa to strengthen it as a barrier against France.

Piedmont was a springboard for Italian unification in 1859–1861, following earlier unsuccessful wars against the Austrian Empire in 1820–1821,[7] and 1848–1849. This process is sometimes referred to as Piedmontisation.[8] The efforts were later countered by the efforts of rural farmers.[9][10] The House of Savoy became Kings of Italy, and Turin briefly became the capital of Italy. However, when the Italian capital was moved to Florence, and then to Rome, the administrative and institutional importance of Piedmont was reduced. The only recognition of Piedmont's historical role was that the crown prince of Italy was known as the Prince of Piedmont. After Italian unification, Piedmont was one of the most important regions in the first Italian industrialization.[11]

-

The Sacra di San Michele is a symbol of Piedmont.

Economy

[edit]The gross domestic product (GDP) of the region was 137.4 billion euros in 2018, accounting for 7.8% of Italy's GDP. GDP per capita at purchasing power parity was 31,300 euros or 104% of the EU27 average in the same year. The GDP per employee was 111% of the EU average.[12] Since 2006, the Piemonte Agency for Investments, Export and Tourism began to facilitate outside investment and promote Piedmont's industry and tourism. It was the first Italian institution to combine the activities being carried out by pre-existing local organizations to promote the territory internationally.

Automotive

[edit]

The region contains major industrial centres, the most important of which is Turin, home to the Fiat conglomerate, but mass-market Fiat cars are not produced anymore, only small-scale manufacturing of luxury Maserati cars (36,702 in 2020). [13] Most of the ex-Fiat plants now belong to other companies: aerospace is owned by Leonardo S.p.A., turbo jet engines by General Electric, high-speed trains by Alstom, bearings by SKF. Fiat does not exist anymore as an independent company; car production belongs to Stellantis, and trucks, buses, tractors, agriculture and construction machines are produced by the independent company CNH Industrial (most manufacturing activity takes place in the United States, in Piedmont only the production of New Holland excavators in San Mauro Torinese and IVECO diesel engines in Turin). Neither of them are headquartered in Turin anymore, however, some research and development centres are still working.

Formerly famous automotive design companies also were sold to global automotive groups: Italdesign Giugiaro to Volkswagen, Ghia to Ford, Pininfarina to Mahindra; Bertone went into bankruptcy in 2014. The massive decline in the automotive industry caused other regions like Veneto (€163 billion in 2018) and Emilia-Romagna (€161 billion in 2018) to surpass Piedmont (€137 billion in 2018) in GDP and led to relative high unemployment. The peak of Italian motor vehicle production is reached in 1989 with 2.22 million units, but in 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy) it was only 0.92 million units. Even existing Italian car production now relocated to South Italy, such as in Pomigliano d'Arco (140,478 in 2020), Melfi (229,848 in 2020), and Atessa (257,026 in 2020), because of cost cutting. [13]

There are some automotive suppliers of:

- exhaust systems, electronic systems, suspension systems and automotive lighting in Venaria Reale and Rivalta di Torino from Magneti Marelli

- dual-clutch transmission, gearboxes, drivelines and their mechatronics components from Dana Graziano

- bearings from SKF

- tires (Michelin and Pirelli)

Electronics and industrial equipment

[edit]There are some important companies in high-tech manufacturing: Comau (industrial robots) and Prima Industrie (laser equipment). Silicon wafer production is in Novara by MEMC. Olivetti, once a major electronics industry whose plants were in Scarmagno and Ivrea, has now turned into a small-scale computer service company and no longer produces computers. Leonardo Elettronica in Turin-Caselle develops and manufactures airborne mission systems and airborne computers. Machine building has a long tradition in Piedmont with the manufacturing of excavators, telescopic handlers, industrial refrigerators, printing machines, paper machines, packaging machines, glass machines, turbines, and high-speed trains.

-

Excavator

New Holland E 215B -

Telescopic Handler Merlo Roto

-

Robot

Comau Aura -

High-speed train

Alstom AGV

Aerospace and defence

[edit]One of the most important industries in Piedmont is military aerospace with plants:

- Leonardo Aircraft Turin-Caselle (Nord and Sud), final assembly of multi-role attack jet Eurofighter Typhoon, ground-attack jet AMX and military transport aircraft C-27J Spartan

- Leonardo Aircraft Novara-Cameri, final assembly of stealth multi-role attack jet Lockheed Martin F-35

- General Electric Avio Aero in Rivalta di Torino, Turin-Sangone, Borgaretto, manufacturing of mechanical transmissions for gas turbine, foundry

Information technology

[edit]Piedmont has several notable IT firms such as Olivetti and Arduino.

Wool textiles

[edit]Italy is the world's largest exporter of carded (71.8% in 2018)[14] and combed (73.4% in 2018)[15] wool fabrics. These are the only two types of fabrics not dominated by Chinese textile exports. There are three industrial districts that process wool in Italy. One of them, Biella, is located in Piedmont.

Below are showed some basic stages of wool processing (not complete).

Jewellery

[edit]One of Italy's four industrial jewellery districts is located in Valenza. Large jewellery companies such as Damiani, Bulgari, and Cartier have factories here as do many other smaller companies.

-

Cartier: Bismarck sapphire necklace

-

Cartier: Mackay emerald and diamond necklace

Agriculture

[edit]

Lowland Piedmont is a fertile agricultural region. The main agricultural products in Piedmont are cereals, including rice, representing more than 10% of national production, maize, grapes for wine-making, fruit and milk.[16] With more than 800,000 head of cattle in 2000, livestock production accounts for half of total agricultural production in Piedmont.

Piedmont is one of the great winegrowing regions in Italy. More than half of its 700 km2 (170,000 acres) of vineyards are registered with DOC designations. It produces prestigious wines as Barolo and Barbaresco from the Langhe near Alba, and the Moscato d'Asti and sparkling Asti from the vineyards around Asti. The city of Asti is about 55 km (34 mi) east of Turin in the plain of the Tanaro River and is one of the most important centres of Montferrat, one of the best known Italian wine districts in the world, declared officially on 22 June 2014 a UNESCO World Heritage site.[17] Indigenous grape varieties include Nebbiolo, Barbera, Dolcetto, Freisa, Grignolino and Brachetto.

Tourism

[edit]

Tourism in Piedmont employs 75,534 people and involves 17,367 companies operating in the hospitality and catering sector, with 1,473 hotels and other tourist accommodation. The sector generates a turnover of €2,671 million, 3.3% of the €80,196 million total estimated spending on tourism in Italy. The region is popular with both foreign visitors and those from other parts of Italy. In 2002 there were 2,651,068 total arrivals, 1,124,696 (42%) of whom were foreign. The traditional leading areas for tourism in Piedmont are the Lake District ("Piedmont's riviera"), which accounts for 32.84% of total overnight stays, and the metropolitan area of Turin, which accounts for 26.51%.[18]

In 2006, Turin hosted the XX Olympic Winter Games, and in 2007 it hosted the XXIII Universiade. Alpine tourism tends to concentrate in a few highly developed stations like Alagna Valsesia and Sestriere. Around 1980, the long-distance trail Grande Traversata delle Alpi (GTA) was created to draw more attention to the variety of remote, sparsely inhabited valleys. Within the tourism industry in Piedmont, a reference to the system of Royal Residences has to be made. First of all, it is part of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites since 1997 and, secondly, it represents a peculiarity of the region, since such a network cannot be found elsewhere in Italy. The Residences of the Royal House of Savoy belong to the historical and cultural heritage of Piedmont and nowadays they play a central role in the tourism field.[19] In a reality in which the tourism industry is characterized by an amalgam of several players and stakeholders, the creation of a system or network like the one of the Royal Residences represents an added benefit for the whole territory as well as a competitive edge.[20] Therefore, considering that tourism is a key factor in the creation of long-lasting value and working in a cooperative and collaborative perspective is essential,[21] the network of the Royal Residences represents an example worth of notice.

Piedmont has many small and picturesque villages, 20 of them have been selected by I Borghi più belli d'Italia (English: The most beautiful Villages of Italy),[22] a non-profit private association of small Italian towns of strong historical and artistic interest,[23] that was founded on the initiative of the Tourism Council of the National Association of Italian Municipalities.[24] These villages are:[25]

- Barolo

- Castagnole delle Lanze

- Cella Monte

- Chianale

- Cocconato

- Garbagna

- Garessio

- Guarene

- Ingria

- Mombaldone

- Monforte d'Alba

- Neive

- Orta San Giulio

- Ostana

- Ricetto di Candelo

- Rosazza

- Usseauso

- Vho

- Vogogna

- Volpedo

Unemployment

[edit]The unemployment rate stood at 6.2% in 2023.[26]

| Year | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unemployment rate | 4.1% | 4.2% | 5.1% | 6.8% | 7.5% | 7.6% | 9.2% | 10.5% | 11.3% | 10.2% | 9.3% | 9.1% | 8.2% | 7.7% | 7.5% | 7.3% | 6.5% | 6.2% |

Transport

[edit]Air

[edit]

Turin-Caselle International Airport has domestic and international flights and handle 3,952,158 passengers and 3,334 tons of cargo in 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic).[16]

Land

[edit]There are links with neighbouring France via the Fréjus and Colle di Tenda tunnels as well as the Montgenèvre Pass. Piedmont also connects with Switzerland by the Simplon and Great St Bernard passes. It is possible to reach Switzerland via a normal road that crosses eastern Piedmont, starting from Arona and ending in Locarno, on the Swiss border. The region has the longest motorway network amongst the Italian regions, covering approximately 800 km (500 mi). It radiates from Turin, connecting it with the other provinces in the region, as well as with the other regions in Italy. In 2001, the number of passenger cars per 1,000 inhabitants was 623 (above the national average of 575).[16] There is a Turin–Milan high-speed railway; the travel time is only 52 minutes.

Education

[edit]

The economy of Piedmont is anchored on a rich history of state support for higher education, including some of the leading universities in Italy. Piedmont is home to the famous University of Turin, the Polytechnic University of Turin, the University of Eastern Piedmont, and more recently the United Nations Interregional Crime and Justice Research Institute.[27]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1861 | 2,759,000 | — |

| 1871 | 2,928,000 | +6.1% |

| 1881 | 3,090,000 | +5.5% |

| 1901 | 3,319,000 | +7.4% |

| 1911 | 3,414,000 | +2.9% |

| 1921 | 3,439,000 | +0.7% |

| 1931 | 3,458,000 | +0.6% |

| 1936 | 3,418,000 | −1.2% |

| 1951 | 3,518,177 | +2.9% |

| 1961 | 3,914,250 | +11.3% |

| 1971 | 4,432,313 | +13.2% |

| 1981 | 4,479,031 | +1.1% |

| 1991 | 4,302,565 | −3.9% |

| 2001 | 4,214,677 | −2.0% |

| 2011 | 4,363,916 | +3.5% |

| 2021 | 4,256,350 | −2.5% |

| Source: ISTAT 2001 | ||

| Country of birth | Population |

|---|---|

| 147,916 | |

| 54,151 | |

| 40,919 | |

| 20,091 | |

| 12,638 | |

| 11,579 | |

| 10,435 | |

| 8,945 | |

| 7,889 | |

| 7,626 | |

| 6,463 | |

| 6,309 | |

| 5,301 | |

| 5,084 |

The population density in Piedmont is lower than the national average. In 2008, it was equal to 174 inhabitants per km2, compared to the national figure of about 200. The Metropolitan City of Turin has 335 inhabitants per km2, whereas Verbano-Cusio-Ossola is the least densely populated province, with 72 inhabitants per km2.[28]

The population of Piedmont followed a downward trend throughout the 1980s, a result of the natural negative balance (of some 3 to 4% per year), while the migratory balance since 1986 has again become positive because of immigration.[28] The population remained stable in the 1990s.

The Turin metro area grew rapidly in the 1950s and 1960s due to an increase of immigrants from southern Italy and Veneto and today it has a population of approximately two million. As of 2008[update], the Italian national institute of statistics (ISTAT) estimated that 310,543 foreign-born immigrants lived in Piedmont, equal to 7.0% of the total regional population. Most immigrants come from Eastern Europe (mostly from Romania, Albania, and Ukraine) with smaller communities of African immigrants.

Government and politics

[edit]The Regional Government (Giunta Regionale) is presided by the president of the region (presidente della regione), who is elected for a five-year term and is composed of the president and 14 ministers, including a vice president (vice presidente).[29] In the 2010 Piedmontese regional election, which took place on 29–30 March, Roberto Cota of Lega Nord defeated incumbent Mercedes Bresso of the Democratic Party (PD). For the 2014 Piedmontese regional election, Cota chose not to stand again for president and the parties composing his coalition failed to agree on a single candidate, resulting in a landslide victory for Sergio Chiamparino, a member of the PD who had been mayor of Turin from 2001 to 2011. Chiamparino was in charge until the 2019 Piedmontese regional election, when Alberto Cirio of Forza Italia became the new president of the region.

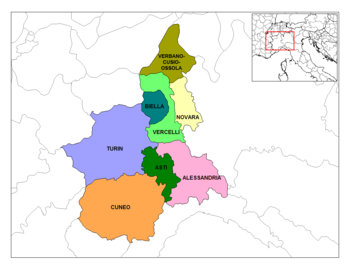

Administrative divisions

[edit]Piedmont is divided into eight provinces.

| Province | Area (km2) | Population | Density (inhabitants/km2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Province of Alessandria | 3,560 | 431,885 | 121.3 |

| Province of Asti | 1,504 | 219,292 | 145.8 |

| Province of Biella | 913 | 181,089 | 204.9 |

| Province of Cuneo | 6,903 | 592,060 | 85.7 |

| Province of Novara | 1,339 | 371,418 | 277.3 |

| Metropolitan City of Turin | 6,821 | 2,291,719 | 335.9 |

| Province of Verbano-Cusio-Ossola | 2,255 | 160,883 | 71.3 |

| Province of Vercelli | 2,088 | 176,121 | 84.3 |

Culture

[edit]Languages

[edit]

As in the rest of Italy, Italian is the official national language. The main local languages are Piedmontese, Insubric (spoken in the eastern part of the region), Occitan (spoken by a minority in the Occitan Valleys situated in the Province of Cuneo and the Metropolitan City of Turin), and Franco-Provençal (spoken by another minority in the alpine heights of the Metropolitan City of Turin), like in the Susa Valley and Walser (spoken by a minority in the Province of Vercelli and Province of Verbano-Cusio-Ossola).

Cuisine

[edit]

Piedmontese cuisine is the style of cooking in the Northern Italian region of Piedmont. Bordering France and Switzerland, Piedmontese cuisine is partly influenced by French cuisine; this is demonstrated in particular by the importance of appetizers, a set of courses that precede what is traditionally called a first course and aimed at whetting the appetite. In France these courses are fewer and are called entrée.[30]

It is a region in Italy with the largest number of cheeses and wines. The most prestigious Italian culinary school, the University of Gastronomic Sciences, was founded in Piedmont. Similar to other Northern Italian cuisines, veal, wine, and butter are among the main ingredients used in cooking.[31]

Some well-known dishes include agnolotti, vitello tonnato (also popular in Argentina), and bagna càuda. Piedmont is also credited for the famous pasta dish tagliolini (tajarin in Piedmontese).[32] Tagliolini are a type of egg pasta normally made fresh by hand. According to Italian writer and journalist Massimo Alberini, tagliolini was among King Victor Emmanuel II's preferred dishes.[33]

Common in Verbano-Cusio-Ossola area[34] are bruscitti, originating from Alto Milanese, a dish of braised meat cut very thin and cooked in wine and fennel seeds, historically obtained by stripping leftover meat.

The Slow Food Movement was started in Piedmont by Carlo Petrini who was from the town of Bra, Piedmont. The movement greatly benefited the region by highlighting Piedmont's diverse cuisine. The Slow Food Movement offices are still headquartered in the town of Bra.

The town of Alba is known for its gourmet food. It is also the region where Alba white truffles are found. [35]

Since 2006, the Piedmont region has benefited from the start of the Slow Food movement and Terra Madre, events that highlighted the rich agricultural and viticultural value of the Po Valley and northern Italy. A chain of food halls Eataly works in collaboration with Slow Food. Piedmont is the leading producer of confectionery, coffee, rice, and white truffles in Italy. It is ranked 3 of 20 for the production of quality DOC and DOCG wines with 1,982,718 hl, there are 17 DOCG wines of all possible types (white, red, sweet, sparkling). In 2019, Piedmont accounted for 16.5% of wine exports from Italy, ranking second behind Veneto, with 36%.[36] The typical food industries in Piedmont are:

- alcoholic beverages

- production of quality dry red wines from Nebbiolo, Dolcetto, and Barbera grapes

- production of quality dry white wines

- production of sweet white wines from Erbaluce grapes

- production of vermouth, which was invented in Piedmont

- production of sparkling wine Asti Spumante, Alta Langa, Gavi

- coffee

- confectionery

- delicacy

- production of white truffles from Alba and related products with white truffles like condiments, honey, salami, and prosciutto

- production of high-quality marinated beef Gradisca or dried beef Bresaola

- cereals

- production of dry risotto mixes

-

White Truffles from Alba

-

Risotto ai funghi porcini

Sport

[edit]

In association football, notable clubs in Piedmont include Turin-based Juventus and Torino, who have won 43 official top-flight league championships (as of the 2020–21 season) between them (36 titles won by Juventus and seven by Torino), more than any other city in Italy. Juventus is the most successful club in Italy, having won the most league titles (36), Coppa Italia titles (14), and Supercoppa Italiana titles (9) of any team in the country; Juventus Women, established in 2017, also achieved success, immediately becoming one of the country's most successful women's teams. Other smaller teams include the old "Piedmont Quadrilateral" components Novara, Alessandria, Casale, and Pro Vercelli. With the pre-World War II success of Pro Vercelli in 1910s and Juventus in 1930s, as well as winning cycles of Torino during the Grande Torino years and Juventus in different eras since 1950, the region became the most successful in terms of championships won. Casale and Novese contributed with one scudetto each. Other local teams include volleyball teams Cuneo (male) and AGIL Novara (female), basketball teams Biella Basketball and Junior Casale, ice hockey team Hockey Club Turin, and roller hockey side Amatori Vercelli, who have won three league titles, an Italian Cup, and two CERS Cups.

Turin hosted the 2006 Winter Olympics.[37] The 2006 Winter Olympics (Italian: 2006 Olimpiadi invernali), officially the XX Olympic Winter Games (Italian: XX Giochi olimpici invernali) and also known as Torino 2006, were a winter multi-sport event held from 10 to 26 February in Turin, Italy. This marked the second time Italy had hosted the Winter Olympics, the first being in 1956 in Cortina d'Ampezzo; Italy had also hosted the Summer Olympics in 1960 in Rome. Turin was selected as the host city for the 2006 Games in June 1999. The official motto of Torino 2006 was "Passion lives here".[38] The Games' logo depicted a stylized profile of the Mole Antonelliana building, drawn in white and blue ice crystals, signifying the snow and the sky. The crystal web was also meant to portray the web of new technologies and the Olympic spirit of community. The 2006 Olympic mascots were Neve ("snow" in Italian), a female snowball, and Gliz, a male ice cube.[39]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Population on 1 January by age, sex and NUTS 2 region", www.ec.europa.eu

- ^ "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 5 March 2023.

- ^ rai (3 June 2015). "An aerial view of Piedmont". Archived from the original on 8 April 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Touring club italiano (1976). Piemonte (non compresa Torino). Touring Editore. p. 11. ISBN 978-88-365-0001-7.

- ^ Rosa, Diego (April 2005). "DIDATTICA - La neve" (PDF). Rivista Ligure di Meteorologia. Società Meteorologica Italiana - Sezione Ligura. p. 3. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- ^ Daftary, Farhad (1990). The Ismāʻı̄lı̄s: Their History and Doctrines. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-37019-1.

- ^ "History of Italy".

- ^ Collier, p. 75.

- ^ Valeria Fargion, From the Southern to the Northern Question: Territorial and Social Politics in Italy Archived 23 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine, paper presented at the RC 19 conference 'Welfare state restructuring: processes and social outcomes', 2–4 September 2004, Sciences-Po Paris. Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ Anna Bull, Regionalism in Italy Archived 10 December 2006 at the Wayback Machine, Europa 2(4). Retrieved 7 January 2007.

- ^ Marco Meriggi, (1996). Breve Storia dell'Italia Settentrionale, dall'Ottocento a Oggi. 1st ed. Italy: Donzelli Dditore, Rome.

- ^ "Regional GDP per capita ranged from 30% to 263% of the EU average in 2018". Eurostat.

- ^ a b "Stellantis production report" (in Italian). 11 January 2021.

- ^ "Who exported Woven fabrics of carded wool in 2018?".

- ^ "Who exported Woven fabrics of combed wool in 2018?".

- ^ a b c "Eurostat". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 10 February 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Vineyard Landscape of Piedmont: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato".

- ^ "Tourism in Piedmont: The Figures" (PDF). Regione Piemonte. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ AA.VV. (2004). Dimore Reali e la Corona di Delizie - Palazzi, castelli e ville sabaude in Piemonte I. Torino: La Stampa. pp. 1–13.

- ^ Cortese, Damiano (2018). L'azienda turistica: nuovi scenari e modelli evolutivi. Torino: Giappichelli Editore. pp. 63–77.

- ^ Cortese D., Giacosa E., Cantino V. (2018). Knowledge sharing for coopetition in tourist destinations: the difficult path to the network. Springer. pp. 1–12.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Basilicata" (in Italian). 10 January 2017. Retrieved 1 August 2023.

- ^ "Borghi più belli d'Italia. Le 14 novità 2023, dal Trentino alla Calabria" (in Italian). 16 January 2023. Retrieved 28 July 2023.

- ^ "I Borghi più belli d'Italia, la guida online ai piccoli centri dell'Italia nascosta" (in Italian). Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- ^ "Piemonte" (in Italian). 9 January 2017. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "Unemployment rates by sex, age, educational attainment level and NUTS 2 regions (%)".

- ^ "Contact Us". www.unicri.it.

- ^ a b "Eurostat". Europa (web portal). Archived from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Sito Ufficiale della Regione Piemonte: Giunta regionale". Regione.piemonte.it. Archived from the original on 18 February 2010. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "Introduzione". La grande cucina regionale - Piemonte (in Italian). Il corriere della sera. 2005.

- ^ Donati, Stella (1979). Il Grande Manuale della Cucina Regionale. Euroclub.

- ^ "Tajarin, a Speciality of Piedmontese Cuisine".

- ^ Alberini, Massimo. Piemontesi a tavola. Itinerario gastronomico da Novara alle Alpi.

- ^ "Antonella Clerici si commuove in diretta. Ciò che succede in studio non la lascia indifferente: il ricordo che emoziona anche il pubblico" (in Italian). 30 November 2020. Retrieved 17 February 2024.

- ^ "Alba White Truffle: what it is and everything you need to know".

- ^ "Export of wine by region in Italy 2019". Statista. Retrieved 4 March 2022.

- ^ "Turin wins 2006 Winter Olympics". Canoe.ca. 19 June 1999. Archived from the original on 10 February 2005. Retrieved 30 June 2023.

- ^ "Italian Passion in the Motto of Torino 2006" (PDF). Torino 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

- ^ "Torino 2006 Mascots". olympic.org. IOC. Archived from the original on 26 May 2010. Retrieved 18 April 2007.

Sources

[edit]- Collier, M. (2003). Italian Unification, 1820–71. Heinemann: Oxford. ISBN 9780435327545.

External links

[edit]- Regional government website (in Italian)

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.